Auto sector needs battery industry to secure its future

Britishvolt may have just been rescued by the Australian company Recharge, and the West Midlands Gigafactory has potential, but it needs an Asian manufacturer quickly, while US and European state funding is making it harder for the independent and nascent UK battery industry to compete. Will Stirling reports.

The British have a deep love for car making, we have it in our bones. Land Rover, Jaguar, MINI, Rolls-Royce, Formula 1, 40+ years of Japanese car production in the UK and much more. But we sure know how to make a mess of the necessary and exciting transition to electric.

Annual UK car production fell -9.8% to 775,014 units in 2022 as global chip shortages and structural changes reduced output. That is about half a million cars down on the pre-pandemic 2019 high of 1.303m. But there were record levels of electrified vehicle (EV) production with almost a third of all cars made fully electric or hybrid – worth £10bn in exports alone, says the car industry body SMMT. Continuing semiconductor shortages and a big loss of volume at two large manufacturers were the drivers.

Despite these challenges, UK factories turned out a record 234,066 battery electric, plug-in hybrid and hybrid electric vehicles with combined volumes up 4.5% year-on-year to represent almost a third (30.2%) of all car production. There are more electric vehicle models on sale in the UK now, with more than 40% of models now available as plug-ins. Most carmakers, including Ford, Nissan, Tesla and Vauxhall have expanded their EV model range to include affordable plug-in models.

But the initial collapse and bounceback of Britishvolt, the UK’s potentially independent, volume battery manufacturer, was a confidence blow to the car industry’s plans to electrify.

The UK needs domestic battery manufacturing. The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the EU and the UK requires that by the end of 2026, batteries in EVs made here must be assembled in the UK or the EU for the vehicle to qualify for tariff-free trade between the two. Shipping heavy, bulky batteries from, for example, Germany or Hungary to be assembled in the UK doesn’t make business sense. While you could argue we’ve done this for years with auto engines and components, today’s cost of fuel, freight and carbon emissions make this plain dumb.

Britishvolt’s volatility has been little surprise to many close to car making; it ran out of money and had no assured customers. Some blamed the government for pulling the £100m Automotive Transformation Fund grant on offer, but Britishvolt failed to pass the tests. There is hope – Australian group Recharge was the preferred bidder to rescue, and it has since stepped in to buy the company and revive the battery manufacturer in Blyth, but auto experts are sceptical. “Recharge has no track record in volume manufacture and, while there is support from a funding consortium, we’re not really sure where the money is coming from,” says Prof David Bailey, Professor of Business Economics at the Birmingham Business School.

Domestic battery capacity of national importance

As demand for EVs rises, and it’s the fastest growing segment of automotive manufacture, the UK needs to build much greater battery capacity.

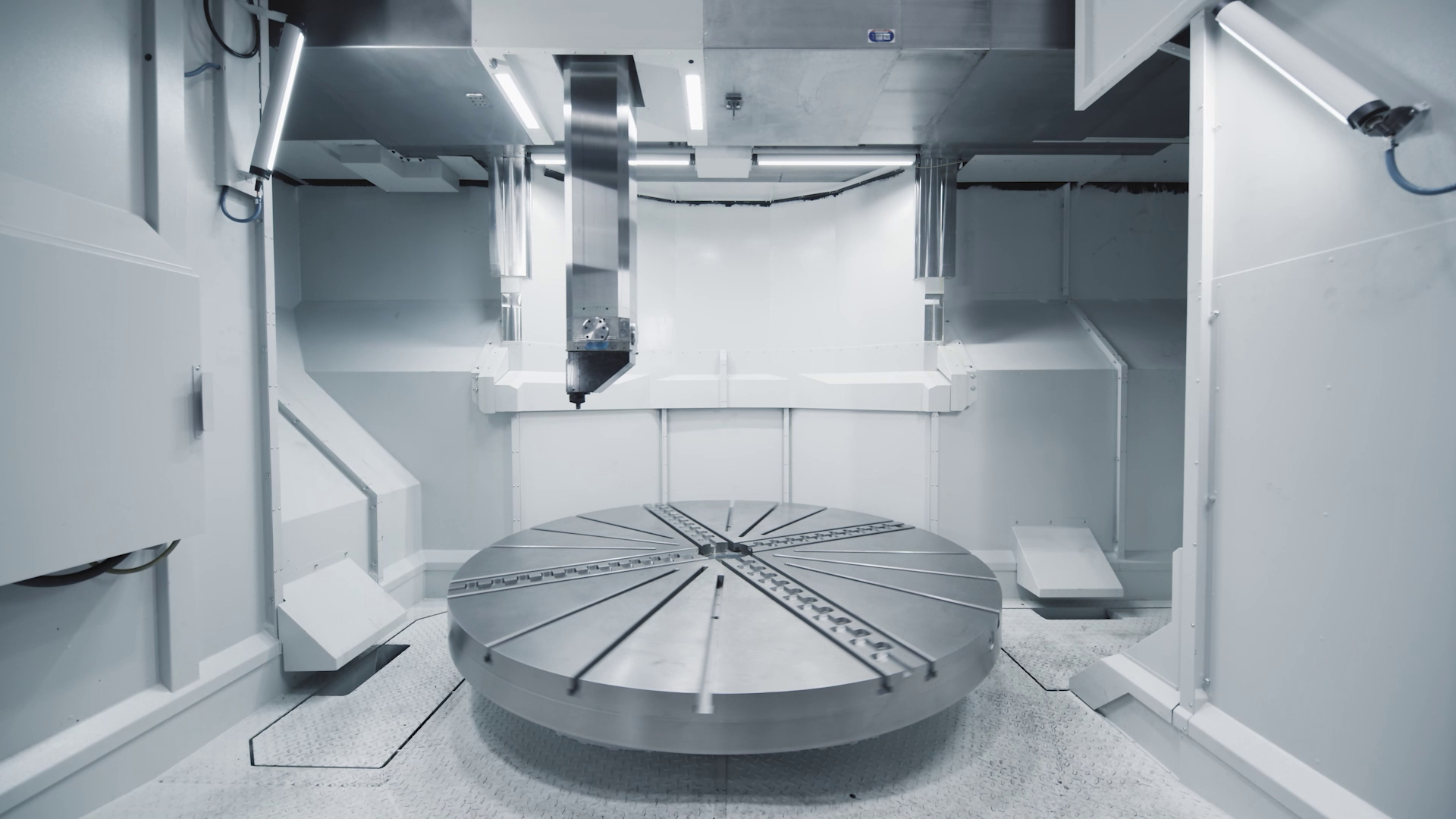

The most viable site is the West Midlands Gigafactory near Coventry City Airport. This is a grand project that will have 60GWh manufacturing capacity, enough to power 600,000 EVs p/a, provide up to 6,000 jobs and is 100% powered by clean energy. The site and planning permission are approved and it will likely apply for a big grant with the Automotive Transformation Fund (ATF). It is backed by Coventry City Council, the West Midlands Combined Authority, The University of Warwick and many more. Its partner page shows an impressive line-up but there is one notable absence – a manufacturing company. Andy Street, mayor of the West Midlands, says several companies are being courted but their identities remain confidential, and any timescale for a decision is either unknown or confidential. The website has South Korean and Chinese language versions, suggesting the candidate’s provenance – they include potentially China’s biggest battery firms CATL and BYD. What the West Midlands Gigafactory must do is secure government backing to sweeten the deal for the Asian investor, likely to be up to 20% of the investment.

“To be clear there is no current application to the ATF for funding, but most governments around the world find that [20%] is the sort of amount they need to offer as a subsidy,” Andy Street told MTD. “It is not unreasonable to think that British government would have to do something similar to secure the gigafactory investment.” But these Asian battery firms are being courted by European countries too.

Here the UK is playing catchup. The European Union has around 35 gigafactories in build or near planning approval and the EU has brought together seven states to support the European Battery Alliance. Funded with around €6bn, its challenging goal is to build a third of global battery cell production capacity in the EU by 2030, serving an estimated €250bn a year market by that time.

In addition, President Biden has launched the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes a gigantic US$369bn of subsidies for green technologies aimed at luring investment – such as EVs and battery manufacture – to the US. The UK finds itself needing to compete with the deep pockets and subsidies of the US, the EU and probably China too, to lure battery makers to Britain. What would help is both an industrial strategy and a UK public sector bank with the reserves to at least offer an alternative to the EIB’s treasure chest. The UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB), set up in 2021, could be such an institution. It is now lending money, but it doesn’t have the powers of a true state bank. “It is still operating in interim form without a full operation in place – the UK Infrastructure Bank Bill aims to put the bank on a statutory footing and clarify its powers,” says David Bailey. The UKIB has funded deals in electricity storage, solar power and digital roll-out, but has not publicly backed the West Midlands Gigafactory or any battery-making project to date, although the head of banking Ian Brown said last October “The UKIB is ready, willing and perfectly placed to support public and private investors to boost EV (development).”

Andy Street is still bullish about the gigafactory’s prospects. “We are strengthening the bid all the time, particularly in the Coventry region, especially with the research and development that has been done, the decisions of companies to bring their R&D here, the sort of skills and talent that we’re producing in our universities – including Warwick Manufacturing Group and Coventry University – that tells me we’ve got a really, really good card.”

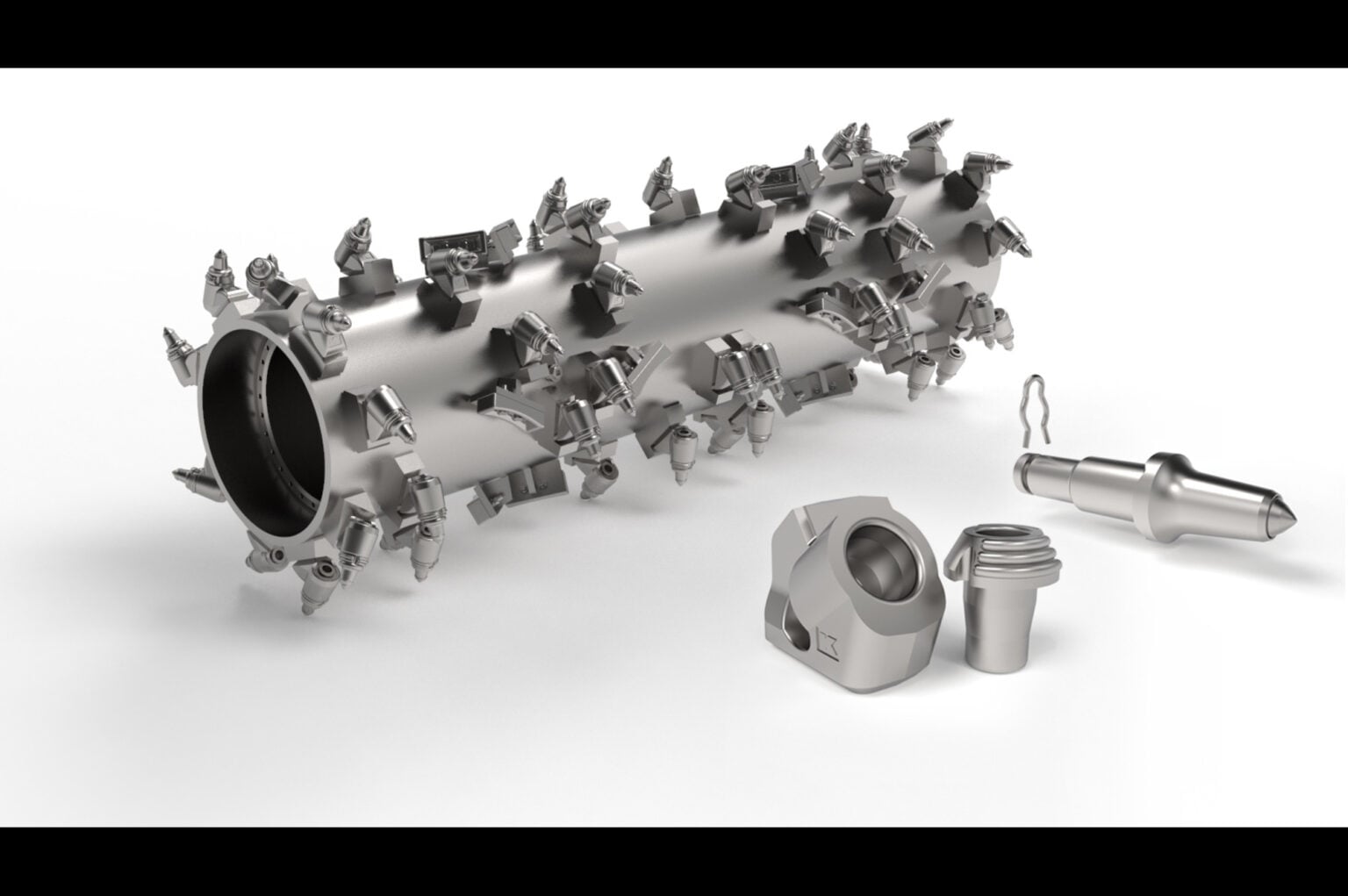

UK supply chain beefs up while battery-making lags behind

Mr Street cites Chinese carmaker Geely’s success with the London Electric Vehicle Company, Triumph Motorcycle’s new Project TE-1 electric motorbike, a consortium with several Midlands companies including Integral Powertrain, recently rebranded as Helix, and Lotus’s success with the Evija hypercar. In fact, there is a huge amount of very positive progress in the development of UK-based electromechanical components electric vehicles, much of it supported by the Advanced Propulsion Centre and a suite of projects, competitions and funds.

In recent months, Equipmake benefitted from the APC’s CELEB2 project, a £7.4m, with £3.7m funded through the APC and match-funded by industry investment, to electrify bus power. This has helped the Norfolk-based powertrain firm and bus maker Agrale to launch a new electric bus in Buenos Aires, Argentina in October, plus a zero-emission double-decker New Routemaster.

Saietta benefitted from the APC’s ADAPT fund to scale up the manufacture of its axial flux motor. And in December, in perhaps the APC’s biggest single round of funding (since Britishvolt collapsed), £73m was provided to five R&D projects to get British low-carbon transportation moving. This included a chunk to Toyota Motor Manufacturing UK to develop a hydrogen-powered Hilux in the UK, to tractor-maker CNH Industrial in Basildon to create the world’s first ‘fugitive liquid’ methane-powered heavy tractor and for HVS, an engineering company in Glasgow, to produce a hydrogen fuel cell-powered HGV cab and tractor unit.

Saietta benefitted from the APC’s ADAPT fund to scale up the manufacture of its axial flux motor. And in December, in perhaps the APC’s biggest single round of funding (since Britishvolt collapsed), £73m was provided to five R&D projects to get British low-carbon transportation moving. This included a chunk to Toyota Motor Manufacturing UK to develop a hydrogen-powered Hilux in the UK, to tractor-maker CNH Industrial in Basildon to create the world’s first ‘fugitive liquid’ methane-powered heavy tractor and for HVS, an engineering company in Glasgow, to produce a hydrogen fuel cell-powered HGV cab and tractor unit.

The UK automotive electric supply chain today feels like the guest list at an important state dinner when the visiting presidents are late. Many smart and high-powered individuals are waiting to network and sow the seeds of big deals but are stuck in slow motion until the guests of honour – in this case, volume battery manufacturing – allow the evening to swing.